What If China's BRI Turns Into A White Elephant In Africa

China is currently Africa's single largest investor and builder of infrastructure because of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). China was attracted to Africa simply because of the abundance of resources, the vast young population, and the low infrastructure capacity that calls for a boost.

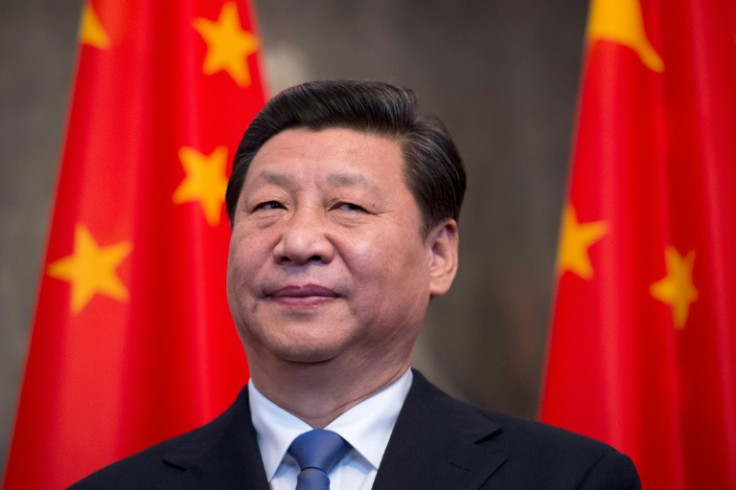

Despite ideological, geographical, and cultural barriers, the BRI, unveiled by Chinese President Xi Jinping in 2013, was a model of integration that aimed to break continental border barriers solely for mutual economic benefits on a larger scale through projects like roadways, airways, and seaways.

During the global financial crisis in 2008, China showed the world how to conduct trade. But after the slowdown, major trade partners decelerated their trade ties with China, which resulted in excess capacity problems, forcing China to seek a new market. And the answer was BRI, touted as the world's biggest infrastructure project, making waves across the globe.

Unlike the Marshall Plan unveiled by the U.S. to help European governments that participated in the Second World War, BRI is not based on aid but loan financing for national projects. That is why the U.S. and the European Union are afraid of losing their leading positions in global trade, which is skewed in their favor currently.

While China has excessive financial savings and a world-class infrastructure capacity, Africa fails on both counts.

Wage comparison is another reason why Africa was shortlisted by China. Way back in 2016, the minimum wage was $300 in Guangdong, a coastal province of southeast China, while in Hawassa Industrial Park in Ethiopia, the average cost of labor was $50 dollars monthly.

For Africa, BRI presented economic prosperity and speedy infrastructural growth and so they wasted no time to be part of this. To their dismay, they found the BRI loan a better alternative compared with the ones offered by the Western axis, which came with a lot of strings attached.

China found the new pastures in Africa good as it ensured benefit in five folds -- returns on loan, patronage of Chinese companies, access to host nations' resources, demographic dividend (young population), and geopolitical and geostrategic accomplishments.

Africa also felt attached to China due to the false notion that China is equally a developing nation, so they are brothers in arms.

As far as Africa was concerned, it too found infrastructure growth and increased production of primary goods with BRI beneficial, though disadvantages like dependency, protracted loan servicing, and the asymmetric nature of the Sino-Africa relations loomed large.

Many African nations already rely on Chinese artificial intelligence networks, and China lords over the smartphone market in Nigeria, the continent's largest market, with more than 200 million cellphone connections.

Chinese companies are active throughout Africa with joint ventures. At the Lekki Free Zone Development Company (LFZDC) in Nigeria; Africa World Airlines (AWA), an air carrier based in Ghana; and the Zinder Refining Company in Niger, where China's major oil firms and companies are calling the shots.

The joint ventures have enabled Chinese cultural adaptation, embracing local management styles, and assimilating local practices and picking up languages commonly spoken in West Africa.

The consultancy firm McKinsey has stated that more than 10,000 Chinese firms operate in Africa and 90 percent of them are private entities that conduct business on their own terms.

Nigeria, Africa's largest economy with large oil and agricultural reserves coupled with a vast young population, fits the bill very much for China.

Although Nigeria has vast natural resources, the West African nation is confronted with infrastructure challenges and funds that match very well with China's appetite for energy.

Nigeria formally joined the BRI in 2018 at the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) Summit in Beijing. The Chinese investments stimulated economic activity in Nigeria and on numerous occasions, the nation's leaders have thanked China for its aid.

However, there are a few contentions. Nigeria's national legislature has lamented the lack of transparency on Chinese loan agreements which are mired in secrecy.

In general, Chinese assistance is tied to Chinese companies, their technology, and capital, which disregard indigenous economic actors. Few Nigerian construction companies play a vital role in BRI projects and so there is less local content in BRI projects, which was corroborated by Nigeria's House of Representative committee on Treaties, Protocols, and Agreements when it looked into local content in BRI projects.

A World Bank report on the BRI noted that the BRI risks– debt sustainability, stranded infrastructure, and damage to local communities and the environment – are exacerbated by weak domestic institutions.

It is not that China will keep money flowing into Africa. China's zero-Covid policy and the property crisis have scaled back BRI lending, leaving African nations high and dry at a time of falling currency values, increasing interest rates, and skyrocketing food and fuel prices. At last year's Forum on China-Africa Cooperation, China declared a $20 billion cut in funding for Africa. Also, experience learned as a lender also played a role in the reduction.

However, because of Africa's long colonial experience that was characterized by exploitation and manipulation, Chinese benevolence has triggered skepticism in many quarters that Africa is once again losing its autonomy as loans under BRI thicken the chain of dependency in multiple folds. Africa will become reliant on Chinese products and technology, just like contemporary Africa is reliant on final goods from Europe, Japan and the U.S.

BRI can satisfy short-term needs, but in the long run, African nations are indebted to China.

After all, BRI is an initiative that is designed to meet the political and economic interests of China and its ruling communist party.

China is aware of Africa's poor debt servicing track record. Is Chinese benevolence in Africa a debt trap and a strategy to loot Africa's resources? What if African nations fail to pay back the loans due to known and unknown factors? Above all, what if the renewed U.S. pushback against China's economic might and China's technological rise destroy the second-largest economy in the world?

Will BRI then turn into a white elephant in Africa?

© Copyright 2025 IBTimes IT. All rights reserved.