Uranium-rich Niger Struggles Despite Nuclear Resurgence

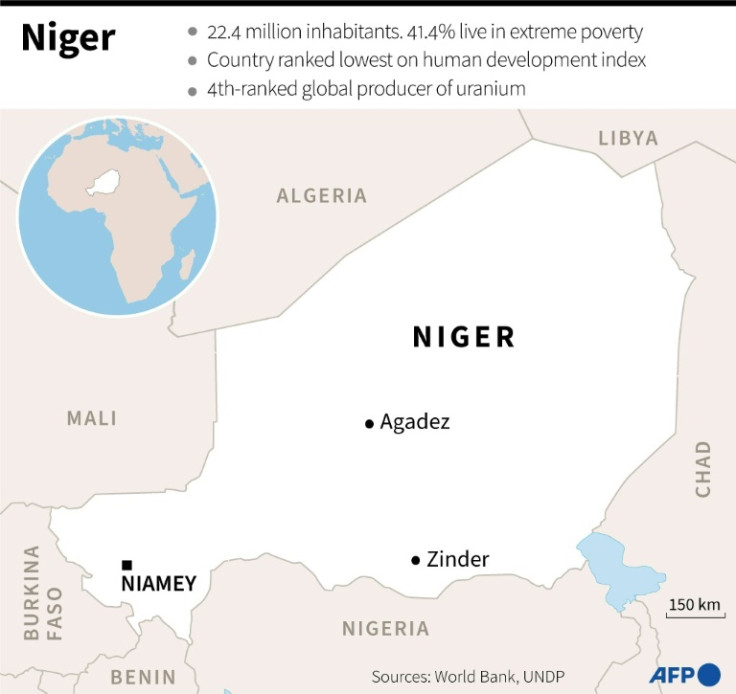

Prospects for the world's nuclear industry have been boosted by the war in Ukraine and mounting hostility towards climate-wrecking fossil fuels -- but Niger, one of the world's biggest sources of uranium, has yet to feel the improvement.

The deeply impoverished landlocked Sahel state is a major supplier of uranium to the European Union, accounting for a fifth of its supplies, and is especially important to France, its former colonial power.

But its mining industry is in the doldrums.

"Over the past few years, the uranium industry worldwide has been marked by a trend of continuously falling prices," Mining Minister Yacouba Hadizatou Ousseini told AFP in an interview.

She blamed "pressure from ecologists" after the 2011 Fukushima nuclear accident in Japan, but also the emergence of "particularly rich deposits" of uranium in Canada for depressing the market.

A concrete example of Niger's problems can be found in its vast mine at Imouraren, which experts had said would yield 5,000 tonnes of ore for 35 years, but which has been closed since 2014.

"Mining at... Imouraren, which is one of the world's largest uranium deposits, will get underway as soon as market conditions permit," French miner Orano, which has the operating licence, says on its website.

Orano, previously known as Areva, has two subsidiaries in Niger.

Last year, its offshoot Cominak wound up activities at a mine in the desert region of Arlit which had been operating since the 1970s after commercially exploitable deposits of uranium ore ran out.

Production at a second site in Arlit by its other subsidiary Somair was 2,000 tonnes in 2021, compared with 3,000 tonnes nine years earlier.

But there is good news, too, for the sector.

Prices have recently been on the upward track over the past two years. At around $50 a pound (half a kilo), they are double the price of six years ago, although still way off the record of $140 per pound, reached during a spike in 2007.

"Prices are low compared to production costs. Many mines have closed because of that," a French uranium expert told AFP.

"But a slow improvement is underway. In the long term, there will be major demand, especially for power stations in Russia or China," the specialist said, asking not to be identified.

This explains why foreign miners -- from Australia, Britain, Canada, China, India, Italy, Russia and the United States -- have been knocking on Niger's door.

"There are 31 current authorisations for uranium prospecting, and 11 permits to mine uranium," the minister said.

On November 5, the Canadian company Global Atomic Corporation began the symbolic start of uranium extraction at a site about 100 kilometres (60 miles) south of Arlit.

It has promised to invest 121 billion CFA francs (around $185 million) there next year.

"(Niger's) uranium... is open to those who have the technological capacity to exploit it," Nigerien President Mohamed Bazoum said last year.

"There is a future for uranium in Niger, but not necessarily with France," the French expert said.

Niger's open-doors policy today contrasts with the half-century entwinement it previously had with France -- a once-cosy relationship that suffered from repeated rows out about pricing.

In 2007, former president Mamadou Tandja successfully fought for a 40-percent increase in price for uranium paid by Areva.

His successor, Mahamadou Issoufou -- a former Areva employee -- once voiced indignation that his country earned so little from uranium, even though it was the fourth biggest producer in the world at the time.

In 2014, Areva and Niger signed a deal, after 18 months of negotiations, that set down improved conditions for Niger through operations at the Imouraren mine.

Those benefits are still awaited, as the huge mine is closed.

"There's no win-win partnership. Niger has had no benefit from uranium mining," said Ali Idrissa, coordinator of a coalition of campaign groups called the Nigerien Network of Organisations for Budget Transparency and Analysis.

Uranium "has brought us only (landscape) desolation... and all the profits went to France," said Nigerien specialist Tchiroma Aissami Mamadou.

In 2020, mining contributed to 1.2 percent of the national budget.

Accusations of abuse or exploitation are rejected by Orano, which said it had invested millions of euros in projects to improve health and education for local communities and spur economic activities around mining sites.

It also pointed to taxes, dividends and other payments that mining companies paid into state coffers, directly or indirectly.

© Copyright AFP 2025. All rights reserved.